15 years of tracking locally unwanted facilities in Canada and the US taught us that there are five key questions you need to answer.

Companies and governments siting new development projects – especially locally unwanted facilities – often face challenges from community opposition. Whether the projects are about resource development or building social infrastructure, such as transportation infrastructure or subsidized housing, navigating public opinion has never been easy.

Many new developments recognize the importance of gathering community acceptance and minimizing public opposition. However, they often find measuring social permission hard. Contrary to a statutory or legal licence, without a set of well-defined measures, many projects are left to exercise their own judgements to determine whether they have the social licence to operate.

Through decades of experience in dealing with a wide variety of challenges related to siting locally unwanted projects, we have developed a practical framework to understand how to communicate with local communities. In our experience, successful siting efforts seek to secure public permission, not public support. People may not like that a gas-fired generating plant or community housing project is being built near them, but if you can answer five key questions, public opinion can accept it as necessary.

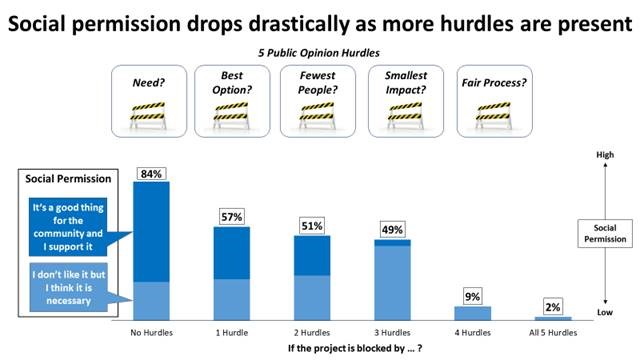

The five hurdles a project needs to cross are:

- Does this project really need to be built?

- Can you not build this project somewhere else?

- Have you done all you can to minimize the number of people directly impacted?

- Have you done all you can to minimize the impact on the people who must be affected (i.e. mitigation, compensation, etc.)?

- Have the people who will be directly affected been treated fairly during this process?

If you can answer yes to each of these questions, you can build permission. If you answer no to any one of these, your project is at risk of being derailed. If any of these hurdles are present, social permission drops drastically. Looking at our latest study in 2019, the intensity of the decrease in social permission has a snowball effect, with the biggest increase in negative feeling shown when a project goes from two hurdles to three.

Often, governments and companies siting locally unwanted facilities make the mistake of thinking it is good enough to have a two-step process before breaking ground: select the site and acquire the permits. After all, if you have a licence to build something somewhere, who cares what people think?

Proponents should care because locally unwanted facilities, like all other building projects, ultimately require social permission to operate. Directly affected people are quick to actively oppose a project, and the broader public can easily and quickly identify with those who will be impacted. As a result, anytime a company or government attempts to build a major project, the proponent runs the risk of walking into a David vs. Goliath media story where the proponent is Goliath. This can result in an environment which creates expensive delays in constructions, a loss of reputational capital, and invites intervention by government.

We are launching our next wave of research this Fall. If you’d like to learn more, or to measure social permission of a project going through a siting process, contact us to discuss how our proprietary data and analysis can provide critical insight in the decisions of your companies, government, or community.